The Earth is Flat Carriage Trade

by Sara Blazej

Edited by Liam Davis

An Artery Exclusive

In a 2013 speech at Georgetown University in Washington D.C., former president Barack Obama addressed a rapt public on the ever worsening climate crisis, cautioning: “We don’t have time for a meeting of the Flat Earth Society. Sticking your head in the sand might make you feel safer but it’s not going to protect you from the coming storm.” Now, with Donald Trump and cohorts at the national helm, it may feel as though we are in that storm in ways we couldn’t have foreseen. Borrowing the tone and rhetoric of Obama’s wry warning, Lower East Side gallery Carriage Trade employs five decades of artworks and centuries-old archival materials in an effort to characterize this atmospheric volatility for their recent seven person exhibition, The Earth Is Flat. The show reflects on the current affective state of politics and culture, ultimately gesturing toward an emerging modern Dark Age in which fear, anger and loss of trust in political powers supplant rational thought, truth and psychological well-being.

Plucked from the annals of canonical art history, Andy Warhol’s disquieting fuschia-hued Electric Chair II, 1971, faces off with four recent gold panels by Henry Codax, who’s own history is rife with fraudulence and misinformation. Codax is a fictional artist in the vein of Reena Spaulings and Claire Fontaine, that is: an invisible figurehead propelled by another artist, or in the latter cases, an artist collective. He first surfaced in the seminal art novel Reena Spaulings, where his likeness may have been fashioned after his rumored creator, Olivier Mosset, the septuagenarian artist who also serves on the gallery’s advisory board.

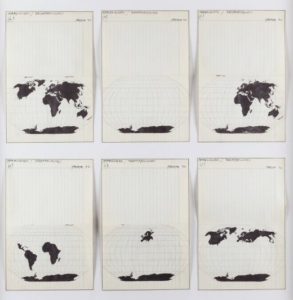

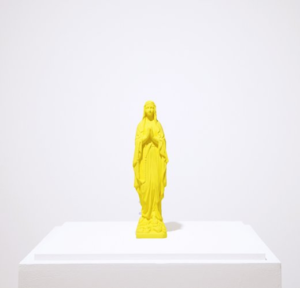

Alongside a projection sculpture by Ceal Floyer and archival prints by Martin Beck, Sara VanDerBeek demonstrates photography’s lack of fixity, and thus documentary reliability, in her diptych of photographic assemblage, Shadow/Moon/Threshold/East, 2015. Nearby, six world maps rendered in graphite on paper, each missing a major land mass, symbolically plot the disappearances of individuals who went missing during Argentina’s Perón regime. The title of this piece by Horatio Zabbala, Apariciones / desapariciones (a,b,c,d,e,f), 1972, translates to Appearances / disappearances. Katharina Fritsch’s yellow Madonna fingers a spiritual shallowness in modern American Christianity, suggesting that the mass reproducibility and aesthetic appeal of the icons is where their true value lies, rather than their spiritual function.

In her book “Depression: A Public Feeling” queer theorist Ann Cvetkovich writes about the notion of “impasse” in the context of societal depression under neoliberalism. She suggests that “as a political category, impasse can be used to describe moments when disagreements and schisms occur within a group or when it’s impossible to imagine how to get to a better future – conditions, for example, of political depression or left melancholy.” When Obama joked that the country didn’t have time for a meeting of the Flat Earth Society, he didn’t so much mean that dissenting voices should be ignored, but that in urgent circumstances, allowing for such schisms to stall action simply allows the danger to grow nearer. The Earth is Flat not only succeeds in representing art’s response to the very conditions we were warned against, but attempts to map we got here, and more importantly, opens thought-lines for moving forward.