by Sara Blazej

Artery Exclusive

Josephine Halvorson presents a new series of paintings and works on paper in her fourth solo show at Sikkema Jenkins in Chelsea. These paintings, oil on linen, are closely cropped scenes of industrial remnants present in the natural area surrounding her home in Brewster, a suburb in Western Massachussetts. Halvorson has taken, as a lyrical framework, the following lost Woody Guthrie verse, apparently omitted from the great anthemic American classic “This Land is Your Land”:As I went walking I saw a sign there / And on the sign it said “No Trespassing.” / But on the other side it didn’t say nothing, / That side was made for you and me.

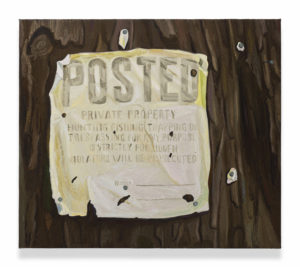

Posted, oil on linen, 25″ x 17″

The populist message of these lyrics coats the show with a lacquer of righteous intention, energizing its content with a jolt of social justice. Halvorson, by attaching these lyrics to her work, seems now to be subtly yet explicitly advocating for a socialist future without private property. One in which the “No Trespassing” signs she lushly renders are merely the traces of a failed social order premised on ownership. But at the same time, the paintings are very likeable on their own, as eerie and expertly produced stand-alone objects.

There is indeed an enticing ghostly quality to the synthetic ruins she finds among the wild of her backyard. Most powerful are her renderings of signs nailed to tree trunks, as in Jagged, Posed and Pale Posted, all 2017. Man-made notices that once screamed from the top of the forrest’s visual hierarchy to halt potential intruders with their bright hue, now are faded and cracked, their aggression quieted by time. Territory markings by humans and animals alike find their place in the story of the local landscape, observed and captured by the artist on walks.

Broadsheet (Threshold), 2017, gouache and silkscreen on paper, 22.5″ x 24.5″

Whether the boundary signs refer to current property lines is unclear, and it is somehow fun to wonder about. One might imagine an scruffy old libertarian thirty or forty years ago, traipsing through the woodlands with his hammer and nails to delineate, with some level of pride and ancestral solidarity, his own private landmass. Then, by contrast, we are drawn into an empathy with the natural elements themselves. In Callus, 2017, we see a tree trunk that has experienced a wound and undergone self-healing, resulting in the namesake of the piece, a callus. It’s a simple, maybe even simplistic, way of reminding us of the damage we do by enforcing claims on the natural world.

Fallen Fence Post, 2017, oil on linen, 17″ x 26″

In the end, Halvorson weaves a surprisingly entrancing pictorial narrative about the relationship between society and land in the United States, focusing on her own locality – working outward from where she stands. Her perspective, though broad and attempting to encompass national issues, remains importantly centered within her town and her practice, which allows her to zoom in and out contextually, while remaining anchored in her own subjectivity.