By Sara Blazej

Artery Exclusive

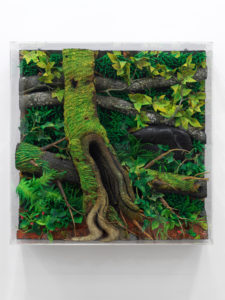

The four person exhibition at Andrew Kreps, including artists Michel Blazy, Piero Galardi, Anika Yi and Tetsumi Kudo, doesn’t have a title, but if it did, it could have taken the name of one of it’s works: Gilardi’s Sottobosco.

Sottobosco, “undergrowth,” also means lowlife, an entity of disreputable and untrustworthy persuasion. An underbelly. In nature, an “undergrowth” is a faction of small trees, bushes and plants growing together under the taller trees in a forest. Something that develops below the surface. In medicine, it refers to a stunting of growth and development, likely due to trauma or a restriction of resources.

The individual practices of the four artists on view align in their consideration of environmental, social and technological concerns. This show, underpinned with the light aroma of current politics, gestures toward these overlapping impetuses, examining where modern technology impresses itself upon the natural world (and vice versa) and tracking biology’s intensifying dance with artifice. The chronological span of the works reminds us that we’ve been talking about the imperiled earth and these relationships for decades, while cooing wisely that though this is a well-worn subject, the clock is ticking on humanity -, and while every media cycle offers us a new more outrageous distraction from bigger picture issues, it is best to not get caught in the weeds.

Gilardi is widely known for his career-long series of polyurethane “Nature carpets,” which consist of the synthetic plastic, meticulously carved and molded into natural scenery such as gardens, rolling beach waves or bramble, as it is in Sottobosco. It is worth noting that the Nature carpets have always been the artist’s most marketable works, despite having formerly been shown as interactive (touchable, walkable) installations. In Gilardi’s recent iterations of the Nature carpets, like the 2008 piece shown at Andrew Krepps, he seems to double down on this fact, de-scaling the scenes and encasing them in plexiglass vitrines, effectively producing vibrant, luscious wallworks that, in a poignant parallel to their subject matter, make precious and elusive what was once durable and abundant.

Ever a master of sensory exhibition design, Anicka Yi presents Deep State, 2017: twin lightboxes, suspended in sleek metal frames, create a false ceiling and an uncomfortable spatial dissociation. The boxes illuminate glowing images of bacteria swabbed from the offices of London’s art gallery Raven Row. Yi’s engagement with micro-organisms is not only a skin-crawling reminder that there are unseen forces at work around, above and below us at all times, but can be read here as an affirmation of the essential roles played by those “behind the scenes” art world administrators: curators, assistants, interns. In this view, the bacilli become bacterial stand-ins for the art office inhabitants around whom the exhibited specimens grow.

There is a noticeable contemporary constituency of artists combining the material strategies of the 1970’s earth artists with those of the Arte Povera movement (like Gilardi), and Michel Blazy is one of the more visible, only he’s been doing it for a couple decades longer. Here he gives us Les Spyrogyres, 1994, a sculptural installation of hanging cotton bundles, melted glue and lentils, which grow throughout the duration of the exhibition, continuing his experimentation with organic matter and the detritus of modern civilization.

The oldest works belong to Tetsumi Kudo, a primary figure in Neo-Dada movement of the 1960’s and 70’s, who died of cancer in 1990. Inside his globular terrarium, Cultivation of Nature & People Who Are Looking At It, 1972, two levels house organic matter like snails, rocks, and strange phallic cactuses, inking virility, or the loss thereof, to the spectre of nuclear war and the impending barrenness of the planet and it’s species.

The exhibition vibrates with the reliable tension inherent in framing natural material within an institutional setting, where the environment is sterile and technology reigns. With its minimal press release and no title, the show too casually engages a truly urgent global issue, but to its credit, does so quite elegantly: every piece is individually gorgeous, with layers of intoxicating scientific fascination, and arranged with room to breathe. In the end, although this may be a missed opportunity for a loud and loaded critical engagement with the environmental crisis there is always poetry in the implicit, the suggested, the subtle hints, the gentle warnings. If anything, this exhibition may simply emblematize a quieting social undertone felt by an exhausted art world and its leftist milieu in the wake of a jarring and dangerous (to the planet and people alike) political year.